2. Reading in data locally and from the web#

2.1. Overview#

In this chapter, you’ll learn to read tabular data of various formats into Python from your local device (e.g., your laptop) and the web. “Reading” (or “loading”) is the process of converting data (stored as plain text, a database, HTML, etc.) into an object (e.g., a data frame) that Python can easily access and manipulate. Thus reading data is the gateway to any data analysis; you won’t be able to analyze data unless you’ve loaded it first. And because there are many ways to store data, there are similarly many ways to read data into Python. The more time you spend upfront matching the data reading method to the type of data you have, the less time you will have to devote to re-formatting, cleaning and wrangling your data (the second step to all data analyses). It’s like making sure your shoelaces are tied well before going for a run so that you don’t trip later on!

2.2. Chapter learning objectives#

By the end of the chapter, readers will be able to do the following:

Define the types of path and use them to locate files:

absolute file path

relative file path

Uniform Resource Locator (URL)

Read data into Python from various types of path using:

read_csvread_excel

Compare and contrast

read_csvandread_excel.Describe when to use the following

read_csvfunction arguments:skiprowssepheadernames

Choose the appropriate

read_csvfunction arguments to load a given plain text tabular data set into Python.Use the

renamefunction to rename columns in a data frame.Use

pandaspackage’sread_excelfunction and arguments to load a sheet from an excel file into Python.Work with databases using functions from the

ibispackage:Connect to a database with

connect.List tables in the database with

list_tables.Create a reference to a database table with

table.Bring data from a database into Python with

execute.

Use

to_csvto save a data frame to a.csvfile.(Optional) Obtain data from the web using scraping and application programming interfaces (APIs):

Read HTML source code from a URL using the

BeautifulSouppackage.Read data from the NASA “Astronomy Picture of the Day” using the

requestspackage.Compare downloading tabular data from a plain text file (e.g.,

.csv), accessing data from an API, and scraping the HTML source code from a website.

2.3. Absolute and relative file paths#

This chapter will discuss the different functions we can use to import data into Python, but before we can talk about how we read the data into Python with these functions, we first need to talk about where the data lives. When you load a data set into Python, you first need to tell Python where those files live. The file could live on your computer (local) or somewhere on the internet (remote).

The place where the file lives on your computer is referred to as its “path”. You can think of the path as directions to the file. There are two kinds of paths: relative paths and absolute paths. A relative path indicates where the file is with respect to your working directory (i.e., “where you are currently”) on the computer. On the other hand, an absolute path indicates where the file is with respect to the computer’s filesystem base (or root) folder, regardless of where you are working.

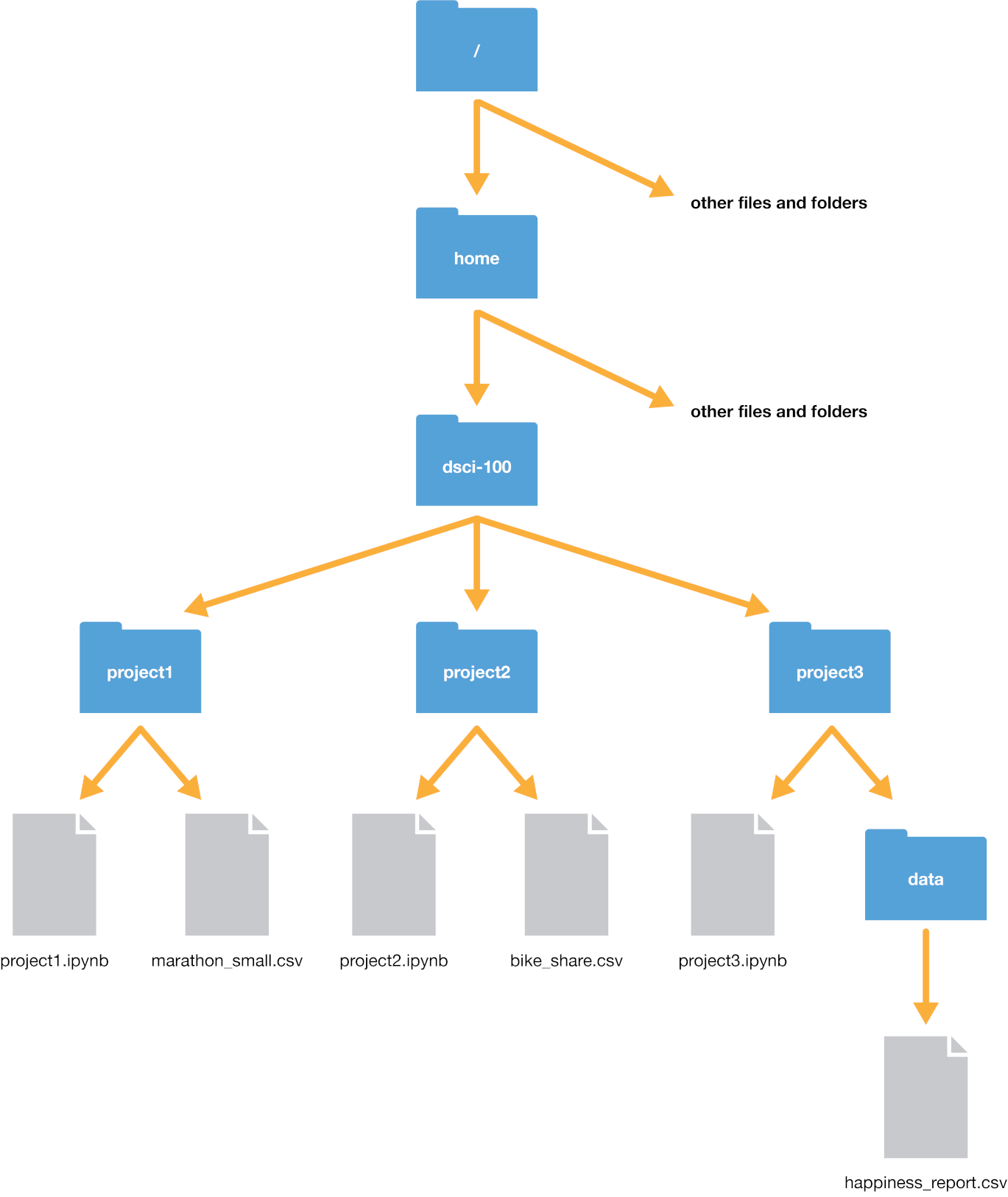

Suppose our computer’s filesystem looks like the picture in

Fig. 2.1. We are working in a

file titled project3.ipynb, and our current working directory is project3;

typically, as is the case here, the working directory is the directory containing the file you are currently

working on.

Fig. 2.1 Example file system#

Let’s say we wanted to open the happiness_report.csv file. We have two options to indicate

where the file is: using a relative path, or using an absolute path.

The absolute path of the file always starts with a slash /—representing the root folder on the computer—and

proceeds by listing out the sequence of folders you would have to enter to reach the file, each separated by another slash /.

So in this case, happiness_report.csv would be reached by starting at the root, and entering the home folder,

then the dsci-100 folder, then the project3 folder, and then finally the data folder. So its absolute

path would be /home/dsci-100/project3/data/happiness_report.csv. We can load the file using its absolute path

as a string passed to the read_csv function from pandas.

happy_data = pd.read_csv("/home/dsci-100/project3/data/happiness_report.csv")

If we instead wanted to use a relative path, we would need to list out the sequence of steps needed to get from our current

working directory to the file, with slashes / separating each step. Since we are currently in the project3 folder,

we just need to enter the data folder to reach our desired file. Hence the relative path is data/happiness_report.csv,

and we can load the file using its relative path as a string passed to read_csv.

happy_data = pd.read_csv("data/happiness_report.csv")

Note that there is no forward slash at the beginning of a relative path; if we accidentally typed "/data/happiness_report.csv",

Python would look for a folder named data in the root folder of the computer—but that doesn’t exist!

Aside from specifying places to go in a path using folder names (like data and project3), we can also specify two additional

special places: the current directory and the previous directory. We indicate the current working directory with a single dot ., and

the previous directory with two dots ... So for instance, if we wanted to reach the bike_share.csv file from the project3 folder, we could

use the relative path ../project2/bike_share.csv. We can even combine these two; for example, we could reach the bike_share.csv file using

the (very silly) path ../project2/../project2/./bike_share.csv with quite a few redundant directions: it says to go back a folder, then open project2,

then go back a folder again, then open project2 again, then stay in the current directory, then finally get to bike_share.csv. Whew, what a long trip!

So which kind of path should you use: relative, or absolute? Generally speaking, you should use relative paths.

Using a relative path helps ensure that your code can be run

on a different computer (and as an added bonus, relative paths are often shorter—easier to type!).

This is because a file’s relative path is often the same across different computers, while a

file’s absolute path (the names of

all of the folders between the computer’s root, represented by /, and the file) isn’t usually the same

across different computers. For example, suppose Fatima and Jayden are working on a

project together on the happiness_report.csv data. Fatima’s file is stored at

/home/Fatima/project3/data/happiness_report.csv

while Jayden’s is stored at

/home/Jayden/project3/data/happiness_report.csv

Even though Fatima and Jayden stored their files in the same place on their

computers (in their home folders), the absolute paths are different due to

their different usernames. If Jayden has code that loads the

happiness_report.csv data using an absolute path, the code won’t work on

Fatima’s computer. But the relative path from inside the project3 folder

(data/happiness_report.csv) is the same on both computers; any code that uses

relative paths will work on both! In the additional resources section,

we include a link to a short video on the

difference between absolute and relative paths.

Beyond files stored on your computer (i.e., locally), we also need a way to locate resources

stored elsewhere on the internet (i.e., remotely). For this purpose we use a

Uniform Resource Locator (URL), i.e., a web address that looks something

like https://python.datasciencebook.ca/. URLs indicate the location of a resource on the internet, and

start with a web domain, followed by a forward slash /, and then a path

to where the resource is located on the remote machine.

2.4. Reading tabular data from a plain text file into Python#

2.4.1. read_csv to read in comma-separated values files#

Now that we have learned about where data could be, we will learn about how

to import data into Python using various functions. Specifically, we will learn how

to read tabular data from a plain text file (a document containing only text)

into Python and write tabular data to a file out of Python. The function we use to do this

depends on the file’s format. For example, in the last chapter, we learned about using

the read_csv function from pandas when reading .csv (comma-separated values)

files. In that case, the separator that divided our columns was a

comma (,). We only learned the case where the data matched the expected defaults

of the read_csv function

(column names are present, and commas are used as the separator between columns).

In this section, we will learn how to read

files that do not satisfy the default expectations of read_csv.

Before we jump into the cases where the data aren’t in the expected default format

for pandas and read_csv, let’s revisit the more straightforward

case where the defaults hold, and the only argument we need to give to the function

is the path to the file, data/can_lang.csv. The can_lang data set contains

language data from the 2016 Canadian census.

We put data/ before the file’s

name when we are loading the data set because this data set is located in a

sub-folder, named data, relative to where we are running our Python code.

Here is what the text in the file data/can_lang.csv looks like.

category,language,mother_tongue,most_at_home,most_at_work,lang_known

Aboriginal languages,"Aboriginal languages, n.o.s.",590,235,30,665

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages,Afrikaans,10260,4785,85,23415

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages,"Afro-Asiatic languages, n.i.e.",1150,44

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages,Akan (Twi),13460,5985,25,22150

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages,Albanian,26895,13135,345,31930

Aboriginal languages,"Algonquian languages, n.i.e.",45,10,0,120

Aboriginal languages,Algonquin,1260,370,40,2480

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages,American Sign Language,2685,3020,1145,21

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages,Amharic,22465,12785,200,33670

And here is a review of how we can use read_csv to load it into Python. First we

load the pandas package to gain access to useful

functions for reading the data.

import pandas as pd

Next we use read_csv to load the data into Python, and in that call we specify the

relative path to the file.

canlang_data = pd.read_csv("data/can_lang.csv")

canlang_data

| category | language | mother_tongue | most_at_home | most_at_work | lang_known | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Aboriginal languages | Aboriginal languages, n.o.s. | 590 | 235 | 30 | 665 |

| 1 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Afrikaans | 10260 | 4785 | 85 | 23415 |

| 2 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Afro-Asiatic languages, n.i.e. | 1150 | 445 | 10 | 2775 |

| 3 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Akan (Twi) | 13460 | 5985 | 25 | 22150 |

| 4 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Albanian | 26895 | 13135 | 345 | 31930 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 209 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Wolof | 3990 | 1385 | 10 | 8240 |

| 210 | Aboriginal languages | Woods Cree | 1840 | 800 | 75 | 2665 |

| 211 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Wu (Shanghainese) | 12915 | 7650 | 105 | 16530 |

| 212 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Yiddish | 13555 | 7085 | 895 | 20985 |

| 213 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Yoruba | 9080 | 2615 | 15 | 22415 |

214 rows × 6 columns

2.4.2. Skipping rows when reading in data#

Oftentimes, information about how data was collected, or other relevant information, is included at the top of the data file. This information is usually written in sentence and paragraph form, with no separator because it is not organized into columns. An example of this is shown below. This information gives the data scientist useful context and information about the data, however, it is not well formatted or intended to be read into a data frame cell along with the tabular data that follows later in the file.

Data source: https://ttimbers.github.io/canlang/

Data originally published in: Statistics Canada Census of Population 2016.

Reproduced and distributed on an as-is basis with their permission.

category,language,mother_tongue,most_at_home,most_at_work,lang_known

Aboriginal languages,"Aboriginal languages, n.o.s.",590,235,30,665

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages,Afrikaans,10260,4785,85,23415

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages,"Afro-Asiatic languages, n.i.e.",1150,445,10,2775

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages,Akan (Twi),13460,5985,25,22150

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages,Albanian,26895,13135,345,31930

Aboriginal languages,"Algonquian languages, n.i.e.",45,10,0,120

Aboriginal languages,Algonquin,1260,370,40,2480

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages,American Sign Language,2685,3020,1145,21930

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages,Amharic,22465,12785,200,33670

With this extra information being present at the top of the file, using

read_csv as we did previously does not allow us to correctly load the data

into Python. In the case of this file, Python just prints a ParserError

message, indicating that it wasn’t able to read the file.

canlang_data = pd.read_csv("data/can_lang_meta-data.csv")

ParserError: Error tokenizing data. C error: Expected 1 fields in line 4, saw 6

To successfully read data like this into Python, the skiprows

argument can be useful to tell Python

how many rows to skip before

it should start reading in the data. In the example above, we would set this

value to 3 to read and load the data correctly.

canlang_data = pd.read_csv("data/can_lang_meta-data.csv", skiprows=3)

canlang_data

| category | language | mother_tongue | most_at_home | most_at_work | lang_known | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Aboriginal languages | Aboriginal languages, n.o.s. | 590 | 235 | 30 | 665 |

| 1 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Afrikaans | 10260 | 4785 | 85 | 23415 |

| 2 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Afro-Asiatic languages, n.i.e. | 1150 | 445 | 10 | 2775 |

| 3 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Akan (Twi) | 13460 | 5985 | 25 | 22150 |

| 4 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Albanian | 26895 | 13135 | 345 | 31930 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 209 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Wolof | 3990 | 1385 | 10 | 8240 |

| 210 | Aboriginal languages | Woods Cree | 1840 | 800 | 75 | 2665 |

| 211 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Wu (Shanghainese) | 12915 | 7650 | 105 | 16530 |

| 212 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Yiddish | 13555 | 7085 | 895 | 20985 |

| 213 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Yoruba | 9080 | 2615 | 15 | 22415 |

214 rows × 6 columns

How did we know to skip three rows? We looked at the data! The first three rows of the data had information we didn’t need to import:

Data source: https://ttimbers.github.io/canlang/

Data originally published in: Statistics Canada Census of Population 2016.

Reproduced and distributed on an as-is basis with their permission.

The column names began at row 4, so we skipped the first three rows.

2.4.3. Using the sep argument for different separators#

Another common way data is stored is with tabs as the separator. Notice the

data file, can_lang.tsv, has tabs in between the columns instead of

commas.

category language mother_tongue most_at_home most_at_work lang_known

Aboriginal languages Aboriginal languages, n.o.s. 590 235 30 665

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages Afrikaans 10260 4785 85 23415

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages Afro-Asiatic languages, n.i.e. 1150 445 10 2775

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages Akan (Twi) 13460 5985 25 22150

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages Albanian 26895 13135 345 31930

Aboriginal languages Algonquian languages, n.i.e. 45 10 0 120

Aboriginal languages Algonquin 1260 370 40 2480

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages American Sign Language 2685 3020 1145 21930

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages Amharic 22465 12785 200 33670

To read in .tsv (tab separated values) files, we can set the sep argument

in the read_csv function to the tab character \t.

Note

\t is an example of an escaped character,

which always starts with a backslash (\).

Escaped characters are used to represent non-printing characters

(like the tab) or characters with special meanings (such as quotation marks).

canlang_data = pd.read_csv("data/can_lang.tsv", sep="\t")

canlang_data

| category | language | mother_tongue | most_at_home | most_at_work | lang_known | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Aboriginal languages | Aboriginal languages, n.o.s. | 590 | 235 | 30 | 665 |

| 1 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Afrikaans | 10260 | 4785 | 85 | 23415 |

| 2 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Afro-Asiatic languages, n.i.e. | 1150 | 445 | 10 | 2775 |

| 3 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Akan (Twi) | 13460 | 5985 | 25 | 22150 |

| 4 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Albanian | 26895 | 13135 | 345 | 31930 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 209 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Wolof | 3990 | 1385 | 10 | 8240 |

| 210 | Aboriginal languages | Woods Cree | 1840 | 800 | 75 | 2665 |

| 211 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Wu (Shanghainese) | 12915 | 7650 | 105 | 16530 |

| 212 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Yiddish | 13555 | 7085 | 895 | 20985 |

| 213 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Yoruba | 9080 | 2615 | 15 | 22415 |

214 rows × 6 columns

If you compare the data frame here to the data frame we obtained in

Section 2.4.1 using read_csv, you’ll notice that they look identical: they have

the same number of columns and rows, the same column names, and the same entries!

So even though we needed to use different

arguments depending on the file format, our resulting data frame

(canlang_data) in both cases was the same.

2.4.4. Using the header argument to handle missing column names#

The can_lang_no_names.tsv file contains a slightly different version

of this data set, except with no column names, and tabs for separators.

Here is how the file looks in a text editor:

Aboriginal languages Aboriginal languages, n.o.s. 590 235 30 665

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages Afrikaans 10260 4785 85 23415

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages Afro-Asiatic languages, n.i.e. 1150 445 10 2775

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages Akan (Twi) 13460 5985 25 22150

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages Albanian 26895 13135 345 31930

Aboriginal languages Algonquian languages, n.i.e. 45 10 0 120

Aboriginal languages Algonquin 1260 370 40 2480

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages American Sign Language 2685 3020 1145 21930

Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages Amharic 22465 12785 200 33670

Data frames in Python need to have column names. Thus if you read in data

without column names, Python will assign names automatically. In this example,

Python assigns the column names 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5.

To read this data into Python, we specify the first

argument as the path to the file (as done with read_csv), and then provide

values to the sep argument (here a tab, which we represent by "\t"),

and finally set header = None to tell pandas that the data file does not

contain its own column names.

canlang_data = pd.read_csv(

"data/can_lang_no_names.tsv",

sep="\t",

header=None

)

canlang_data

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Aboriginal languages | Aboriginal languages, n.o.s. | 590 | 235 | 30 | 665 |

| 1 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Afrikaans | 10260 | 4785 | 85 | 23415 |

| 2 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Afro-Asiatic languages, n.i.e. | 1150 | 445 | 10 | 2775 |

| 3 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Akan (Twi) | 13460 | 5985 | 25 | 22150 |

| 4 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Albanian | 26895 | 13135 | 345 | 31930 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 209 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Wolof | 3990 | 1385 | 10 | 8240 |

| 210 | Aboriginal languages | Woods Cree | 1840 | 800 | 75 | 2665 |

| 211 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Wu (Shanghainese) | 12915 | 7650 | 105 | 16530 |

| 212 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Yiddish | 13555 | 7085 | 895 | 20985 |

| 213 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Yoruba | 9080 | 2615 | 15 | 22415 |

214 rows × 6 columns

It is best to rename your columns manually in this scenario. The current column names

(0, 1, etc.) are problematic for two reasons: first, because they not very descriptive names, which will make your analysis

confusing; and second, because your column names should generally be strings, but are currently integers.

To rename your columns, you can use the rename function

from the pandas package.

The argument of the rename function is columns, which takes a mapping between the old column names and the new column names.

In this case, we want to rename the old columns (0, 1, ..., 5) in the canlang_data data frame to more descriptive names.

To specify the mapping, we create a dictionary: a Python object that represents

a mapping from keys to values. We can create a dictionary by using a pair of curly

braces { }, and inside the braces placing pairs of key : value separated by commas.

Below, we create a dictionary called col_map that maps the old column names in canlang_data to new column

names, and then pass it to the rename function.

col_map = {

0 : "category",

1 : "language",

2 : "mother_tongue",

3 : "most_at_home",

4 : "most_at_work",

5 : "lang_known"

}

canlang_data_renamed = canlang_data.rename(columns=col_map)

canlang_data_renamed

| category | language | mother_tongue | most_at_home | most_at_work | lang_known | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Aboriginal languages | Aboriginal languages, n.o.s. | 590 | 235 | 30 | 665 |

| 1 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Afrikaans | 10260 | 4785 | 85 | 23415 |

| 2 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Afro-Asiatic languages, n.i.e. | 1150 | 445 | 10 | 2775 |

| 3 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Akan (Twi) | 13460 | 5985 | 25 | 22150 |

| 4 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Albanian | 26895 | 13135 | 345 | 31930 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 209 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Wolof | 3990 | 1385 | 10 | 8240 |

| 210 | Aboriginal languages | Woods Cree | 1840 | 800 | 75 | 2665 |

| 211 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Wu (Shanghainese) | 12915 | 7650 | 105 | 16530 |

| 212 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Yiddish | 13555 | 7085 | 895 | 20985 |

| 213 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Yoruba | 9080 | 2615 | 15 | 22415 |

214 rows × 6 columns

The column names can also be assigned to the data frame immediately upon reading it from the file by passing a

list of column names to the names argument in read_csv.

canlang_data = pd.read_csv(

"data/can_lang_no_names.tsv",

sep="\t",

header=None,

names=[

"category",

"language",

"mother_tongue",

"most_at_home",

"most_at_work",

"lang_known",

],

)

canlang_data

| category | language | mother_tongue | most_at_home | most_at_work | lang_known | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Aboriginal languages | Aboriginal languages, n.o.s. | 590 | 235 | 30 | 665 |

| 1 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Afrikaans | 10260 | 4785 | 85 | 23415 |

| 2 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Afro-Asiatic languages, n.i.e. | 1150 | 445 | 10 | 2775 |

| 3 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Akan (Twi) | 13460 | 5985 | 25 | 22150 |

| 4 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Albanian | 26895 | 13135 | 345 | 31930 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 209 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Wolof | 3990 | 1385 | 10 | 8240 |

| 210 | Aboriginal languages | Woods Cree | 1840 | 800 | 75 | 2665 |

| 211 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Wu (Shanghainese) | 12915 | 7650 | 105 | 16530 |

| 212 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Yiddish | 13555 | 7085 | 895 | 20985 |

| 213 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Yoruba | 9080 | 2615 | 15 | 22415 |

214 rows × 6 columns

2.4.5. Reading tabular data directly from a URL#

We can also use read_csv to read in data directly from a Uniform Resource Locator (URL) that

contains tabular data. Here, we provide the URL of a remote file

to read_csv, instead of a path to a local file on our

computer. We need to surround the URL with quotes similar to when we specify a

path on our local computer. All other arguments that we use are the same as

when using these functions with a local file on our computer.

url = "https://raw.githubusercontent.com/UBC-DSCI/introduction-to-datascience-python/reading/source/data/can_lang.csv"

pd.read_csv(url)

canlang_data = pd.read_csv(url)

canlang_data

| category | language | mother_tongue | most_at_home | most_at_work | lang_known | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Aboriginal languages | Aboriginal languages, n.o.s. | 590 | 235 | 30 | 665 |

| 1 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Afrikaans | 10260 | 4785 | 85 | 23415 |

| 2 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Afro-Asiatic languages, n.i.e. | 1150 | 445 | 10 | 2775 |

| 3 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Akan (Twi) | 13460 | 5985 | 25 | 22150 |

| 4 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Albanian | 26895 | 13135 | 345 | 31930 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 209 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Wolof | 3990 | 1385 | 10 | 8240 |

| 210 | Aboriginal languages | Woods Cree | 1840 | 800 | 75 | 2665 |

| 211 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Wu (Shanghainese) | 12915 | 7650 | 105 | 16530 |

| 212 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Yiddish | 13555 | 7085 | 895 | 20985 |

| 213 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Yoruba | 9080 | 2615 | 15 | 22415 |

214 rows × 6 columns

2.4.6. Previewing a data file before reading it into Python#

In many of the examples above, we gave you previews of the data file before we read it into Python. Previewing data is essential to see whether or not there are column names, what the separators are, and if there are rows you need to skip. You should do this yourself when trying to read in data files: open the file in whichever text editor you prefer to inspect its contents prior to reading it into Python.

2.5. Reading tabular data from a Microsoft Excel file#

There are many other ways to store tabular data sets beyond plain text files,

and similarly, many ways to load those data sets into Python. For example, it is

very common to encounter, and need to load into Python, data stored as a Microsoft

Excel spreadsheet (with the file name

extension .xlsx). To be able to do this, a key thing to know is that even

though .csv and .xlsx files look almost identical when loaded into Excel,

the data themselves are stored completely differently. While .csv files are

plain text files, where the characters you see when you open the file in a text

editor are exactly the data they represent, this is not the case for .xlsx

files. Take a look at a snippet of what a .xlsx file would look like in a text editor:

,?'O

_rels/.rels???J1??>E?{7?

<?V????w8?'J???'QrJ???Tf?d??d?o?wZ'???@>?4'?|??hlIo??F

t 8f??3wn

????t??u"/

%~Ed2??<?w??

?Pd(??J-?E???7?'t(?-GZ?????y???c~N?g[^_r?4

yG?O

?K??G?

]TUEe??O??c[???????6q??s??d?m???\???H?^????3} ?rZY? ?:L60?^?????XTP+?|?

X?a??4VT?,D?Jq

This type of file representation allows Excel files to store additional things

that you cannot store in a .csv file, such as fonts, text formatting,

graphics, multiple sheets and more. And despite looking odd in a plain text

editor, we can read Excel spreadsheets into Python using the pandas package’s read_excel

function developed specifically for this

purpose.

canlang_data = pd.read_excel("data/can_lang.xlsx")

canlang_data

| category | language | mother_tongue | most_at_home | most_at_work | lang_known | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Aboriginal languages | Aboriginal languages, n.o.s. | 590 | 235 | 30 | 665 |

| 1 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Afrikaans | 10260 | 4785 | 85 | 23415 |

| 2 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Afro-Asiatic languages, n.i.e. | 1150 | 445 | 10 | 2775 |

| 3 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Akan (Twi) | 13460 | 5985 | 25 | 22150 |

| 4 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Albanian | 26895 | 13135 | 345 | 31930 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 209 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Wolof | 3990 | 1385 | 10 | 8240 |

| 210 | Aboriginal languages | Woods Cree | 1840 | 800 | 75 | 2665 |

| 211 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Wu (Shanghainese) | 12915 | 7650 | 105 | 16530 |

| 212 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Yiddish | 13555 | 7085 | 895 | 20985 |

| 213 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Yoruba | 9080 | 2615 | 15 | 22415 |

214 rows × 6 columns

If the .xlsx file has multiple sheets, you have to use the sheet_name argument

to specify the sheet number or name. This functionality is useful when a single sheet contains

multiple tables (a sad thing that happens to many Excel spreadsheets since this

makes reading in data more difficult). You can also specify cell ranges using the

usecols argument (e.g., usecols="A:D" for including columns from A to D).

As with plain text files, you should always explore the data file before importing it into Python. Exploring the data beforehand helps you decide which arguments you need to load the data into Python successfully. If you do not have the Excel program on your computer, you can use other programs to preview the file. Examples include Google Sheets and Libre Office.

In Table 2.1 we summarize the read_csv and read_excel functions we covered

in this chapter. We also include the arguments for data separated by

semicolons ;, which you may run into with data sets where the decimal is

represented by a comma instead of a period (as with some data sets from

European countries).

Data File Type |

Python Function |

Arguments |

|---|---|---|

Comma ( |

|

just the file path |

Tab ( |

|

|

Missing header |

|

|

European-style numbers, semicolon ( |

|

|

Excel files ( |

|

|

2.6. Reading data from a database#

Another very common form of data storage is the relational database. Databases are great when you have large data sets or multiple users working on a project. There are many relational database management systems, such as SQLite, MySQL, PostgreSQL, Oracle, and many more. These different relational database management systems each have their own advantages and limitations. Almost all employ SQL (structured query language) to obtain data from the database. But you don’t need to know SQL to analyze data from a database; several packages have been written that allow you to connect to relational databases and use the Python programming language to obtain data. In this book, we will give examples of how to do this using Python with SQLite and PostgreSQL databases.

2.6.1. Reading data from a SQLite database#

SQLite is probably the simplest relational database system

that one can use in combination with Python. SQLite databases are self-contained, and are

usually stored and accessed locally on one computer from

a file with a .db extension (or sometimes a .sqlite extension).

Similar to Excel files, these are not plain text files and cannot be read in a plain text editor.

The first thing you need to do to read data into Python from a database is to

connect to the database. For an SQLite database, we will do that using

the connect function from the

sqlite backend in the

ibis package. This command does not read

in the data, but simply tells Python where the database is and opens up a

communication channel that Python can use to send SQL commands to the database.

Note

There is another database package in python called sqlalchemy.

That package is a bit more mature than ibis,

so if you want to dig deeper into working with databases in Python, that is a good next

package to learn about. We will work with ibis in this book, as it

provides a more modern and friendlier syntax that is more like pandas for data analysis code.

import ibis

conn = ibis.sqlite.connect("data/can_lang.db")

Often relational databases have many tables; thus, in order to retrieve

data from a database, you need to know the name of the table

in which the data is stored. You can get the names of

all the tables in the database using the list_tables

function:

tables = conn.list_tables()

tables

['can_lang']

The list_tables function returned only one name—"can_lang"—which tells us

that there is only one table in this database. To reference a table in the

database (so that we can perform operations like selecting columns and filtering rows), we

use the table function from the conn object. The object returned

by the table function allows us to work with data

stored in databases as if they were just regular pandas data frames; but secretly, behind

the scenes, ibis will turn your commands into SQL queries!

canlang_table = conn.table("can_lang")

canlang_table

DatabaseTable: can_lang category string language string mother_tongue float64 most_at_home float64 most_at_work float64 lang_known float64

Although it looks like we might have obtained the whole data frame from the database, we didn’t!

It’s a reference; the data is still stored only in the SQLite database. The canlang_table object

is a DatabaseTable, which, when printed, tells

you which columns are available in the table. But unlike a usual pandas data frame,

we do not immediately know how many rows are in the table. In order to find out how many

rows there are, we have to send an SQL query (i.e., command) to the data base.

In ibis, we can do that using the count function from the table object.

canlang_table.count()

r0 := DatabaseTable: can_lang

category string

language string

mother_tongue float64

most_at_home float64

most_at_work float64

lang_known float64

CountStar(can_lang): CountStar(r0)

Wait a second…this isn’t the number of rows in the database. In fact, we haven’t actually sent our

SQL query to the database yet! We need to explicitly tell ibis when we want to send the query.

The reason for this is that databases are often more efficient at working with (i.e., selecting, filtering,

joining, etc.) large data sets than Python. And typically, the database will not even

be stored on your computer, but rather a more powerful machine somewhere on the

web. So ibis is lazy and waits to bring this data into memory until you explicitly

tell it to using the execute function. The execute function actually sends the SQL query

to the database, and gives you the result. Let’s look at the number of rows in the table by executing

the count command.

canlang_table.count().execute()

214

There we go! There are 214 rows in the can_lang table. If you are interested in seeing

the actual text of the SQL query that ibis sends to the database, you can use the compile function

instead of execute. But note that you have to pass the result of compile to the str function to turn it into

a human-readable string first.

str(canlang_table.count().compile())

'SELECT count(*) AS "CountStar(can_lang)" \nFROM can_lang AS t0'

The output above shows the SQL code that is sent to the database. When we

write canlang_table.count().execute() in Python, in the background, the execute function is

translating the Python code into SQL, sending that SQL to the database, and then translating the

response for us. So ibis does all the hard work of translating from Python to SQL and back for us;

we can just stick with Python!

The ibis package provides lots of pandas-like tools for working with database tables.

For example, we can look at the first few rows of the table by using the head function,

followed by execute to retrieve the response.

canlang_table.head(10).execute()

| category | language | mother_tongue | most_at_home | most_at_work | lang_known | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Aboriginal languages | Aboriginal languages, n.o.s. | 590.0 | 235.0 | 30.0 | 665.0 |

| 1 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Afrikaans | 10260.0 | 4785.0 | 85.0 | 23415.0 |

| 2 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Afro-Asiatic languages, n.i.e. | 1150.0 | 445.0 | 10.0 | 2775.0 |

| 3 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Akan (Twi) | 13460.0 | 5985.0 | 25.0 | 22150.0 |

| 4 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Albanian | 26895.0 | 13135.0 | 345.0 | 31930.0 |

| 5 | Aboriginal languages | Algonquian languages, n.i.e. | 45.0 | 10.0 | 0.0 | 120.0 |

| 6 | Aboriginal languages | Algonquin | 1260.0 | 370.0 | 40.0 | 2480.0 |

| 7 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | American Sign Language | 2685.0 | 3020.0 | 1145.0 | 21930.0 |

| 8 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Amharic | 22465.0 | 12785.0 | 200.0 | 33670.0 |

| 9 | Non-Official & Non-Aboriginal languages | Arabic | 419890.0 | 223535.0 | 5585.0 | 629055.0 |

You can see that ibis actually returned a pandas data frame to us after we executed the query,

which is very convenient for working with the data after getting it from the database.

So now that we have the canlang_table table reference for the 2016 Canadian Census data in hand, we

can mostly continue onward as if it were a regular data frame. For example, let’s do the same exercise

from Chapter 1: we will obtain only those rows corresponding to Aboriginal languages, and keep only

the language and mother_tongue columns.

We can use the [] operation with a logical statement

to obtain only certain rows. Below we filter the data to include only Aboriginal languages.

canlang_table_filtered = canlang_table[canlang_table["category"] == "Aboriginal languages"]

canlang_table_filtered

r0 := DatabaseTable: can_lang

category string

language string

mother_tongue float64

most_at_home float64

most_at_work float64

lang_known float64

Selection[r0]

predicates:

r0.category == 'Aboriginal languages'

Above you can see that we have not yet executed this command; canlang_table_filtered is just showing

the first part of our query (the part that starts with Selection[r0] above).

We didn’t call execute because we are not ready to bring the data into Python yet.

We can still use the database to do some work to obtain only the small amount of data we want to work with locally

in Python. Let’s add the second part of our SQL query: selecting only the language and mother_tongue columns.

canlang_table_selected = canlang_table_filtered[["language", "mother_tongue"]]

canlang_table_selected

r0 := DatabaseTable: can_lang

category string

language string

mother_tongue float64

most_at_home float64

most_at_work float64

lang_known float64

r1 := Selection[r0]

predicates:

r0.category == 'Aboriginal languages'

Selection[r1]

selections:

language: r1.language

mother_tongue: r1.mother_tongue

Now you can see that the ibis query will have two steps: it will first find rows corresponding to

Aboriginal languages, then it will extract only the language and mother_tongue columns that we are interested in.

Let’s actually execute the query now to bring the data into Python as a pandas data frame, and print the result.

aboriginal_lang_data = canlang_table_selected.execute()

aboriginal_lang_data

| language | mother_tongue | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Aboriginal languages, n.o.s. | 590.0 |

| 1 | Algonquian languages, n.i.e. | 45.0 |

| 2 | Algonquin | 1260.0 |

| 3 | Athabaskan languages, n.i.e. | 50.0 |

| 4 | Atikamekw | 6150.0 |

| ... | ... | ... |

| 62 | Thompson (Ntlakapamux) | 335.0 |

| 63 | Tlingit | 95.0 |

| 64 | Tsimshian | 200.0 |

| 65 | Wakashan languages, n.i.e. | 10.0 |

| 66 | Woods Cree | 1840.0 |

67 rows × 2 columns

ibis provides many more functions (not just the [] operation)

that you can use to manipulate the data within the database before calling

execute to obtain the data in Python. But ibis does not provide every function

that we need for analysis; we do eventually need to call execute.

For example, ibis does not provide the tail function to look at the last

rows in a database, even though pandas does.

canlang_table_selected.tail(6)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

AttributeError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[24], line 1

----> 1 canlang_table_selected.tail(6)

File /opt/conda/lib/python3.11/site-packages/ibis/expr/types/relations.py:645, in Table.__getattr__(self, key)

641 hint = common_typos[key]

642 raise AttributeError(

643 f"{type(self).__name__} object has no attribute {key!r}, did you mean {hint!r}"

644 )

--> 645 raise AttributeError(f"'Table' object has no attribute {key!r}")

AttributeError: 'Table' object has no attribute 'tail'

aboriginal_lang_data.tail(6)

| language | mother_tongue | |

|---|---|---|

| 61 | Tahltan | 95.0 |

| 62 | Thompson (Ntlakapamux) | 335.0 |

| 63 | Tlingit | 95.0 |

| 64 | Tsimshian | 200.0 |

| 65 | Wakashan languages, n.i.e. | 10.0 |

| 66 | Woods Cree | 1840.0 |

So once you have finished your data wrangling of the database reference object, it is advisable to

bring it into Python as a pandas data frame using the execute function.

But be very careful using execute: databases are often very big,

and reading an entire table into Python might take a long time to run or even possibly

crash your machine. So make sure you select and filter the database table

to reduce the data to a reasonable size before using execute to read it into Python!

2.6.2. Reading data from a PostgreSQL database#

PostgreSQL (also called Postgres) is a very popular

and open-source option for relational database software.

Unlike SQLite,

PostgreSQL uses a client–server database engine, as it was designed to be used

and accessed on a network. This means that you have to provide more information

to Python when connecting to Postgres databases. The additional information that you

need to include when you call the connect function is listed below:

database: the name of the database (a single PostgreSQL instance can host more than one database)host: the URL pointing to where the database is located (localhostif it is on your local machine)port: the communication endpoint between Python and the PostgreSQL database (usually5432)user: the username for accessing the databasepassword: the password for accessing the database

Below we demonstrate how to connect to a version of

the can_mov_db database, which contains information about Canadian movies.

Note that the host (fakeserver.stat.ubc.ca), user (user0001), and

password (abc123) below are not real; you will not actually

be able to connect to a database using this information.

conn = ibis.postgres.connect(

database="can_mov_db",

host="fakeserver.stat.ubc.ca",

port=5432,

user="user0001",

password="abc123"

)

Aside from needing to provide that additional information, ibis makes it so

that connecting to and working with a Postgres database is identical to

connecting to and working with an SQLite database. For example, we can again use

list_tables to find out what tables are in the can_mov_db database:

conn.list_tables()

["themes", "medium", "titles", "title_aliases", "forms", "episodes", "names", "names_occupations", "occupation", "ratings"]

We see that there are 10 tables in this database. Let’s first look at the

"ratings" table to find the lowest rating that exists in the can_mov_db

database.

ratings_table = conn.table("ratings")

ratings_table

AlchemyTable: ratings

title string

average_rating float64

num_votes int64

To find the lowest rating that exists in the data base, we first need to

select the average_rating column:

avg_rating = ratings_table[["average_rating"]]

avg_rating

r0 := AlchemyTable: ratings

title string

average_rating float64

num_votes int64

Selection[r0]

selections:

average_rating: r0.average_rating

Next we use the order_by function from ibis order the table by average_rating,

and then the head function to select the first row (i.e., the lowest score).

lowest = avg_rating.order_by("average_rating").head(1)

lowest.execute()

| average_rating | |

|---|---|

| 0 | 1.0 |

We see the lowest rating given to a movie is 1, indicating that it must have been a really bad movie…

2.6.3. Why should we bother with databases at all?#

Opening a database involved a lot more effort than just opening a .csv, or any of the

other plain text or Excel formats. We had to open a connection to the database,

then use ibis to translate pandas-like

commands (the [] operation, head, etc.) into SQL queries that the database

understands, and then finally execute them. And not all pandas commands can currently be translated

via ibis into database queries. So you might be wondering: why should we use

databases at all?

Databases are beneficial in a large-scale setting:

They enable storing large data sets across multiple computers with backups.

They provide mechanisms for ensuring data integrity and validating input.

They provide security and data access control.

They allow multiple users to access data simultaneously and remotely without conflicts and errors. For example, there are billions of Google searches conducted daily in 2021 [Real Time Statistics Project, 2021]. Can you imagine if Google stored all of the data from those searches in a single

.csvfile!? Chaos would ensue!

2.7. Writing data from Python to a .csv file#

At the middle and end of a data analysis, we often want to write a data frame

that has changed (through selecting columns, filtering rows, etc.)

to a file to share it with others or use it for another step in the analysis.

The most straightforward way to do this is to use the to_csv function

from the pandas package. The default

arguments are to use a comma (,) as the separator, and to include column names

in the first row. We also specify index = False to tell pandas not to print

row numbers in the .csv file. Below we demonstrate creating a new version of the Canadian

languages data set without the “Official languages” category according to the

Canadian 2016 Census, and then writing this to a .csv file:

no_official_lang_data = canlang_data[canlang_data["category"] != "Official languages"]

no_official_lang_data.to_csv("data/no_official_languages.csv", index=False)

2.8. Obtaining data from the web#

Note

This section is not required reading for the remainder of the textbook. It is included for those readers interested in learning a little bit more about how to obtain different types of data from the web.

Data doesn’t just magically appear on your computer; you need to get it from

somewhere. Earlier in the chapter we showed you how to access data stored in a

plain text, spreadsheet-like format (e.g., comma- or tab-separated) from a web

URL using the read_csv function from pandas. But as time goes on, it is

increasingly uncommon to find data (especially large amounts of data) in this

format available for download from a URL. Instead, websites now often offer

something known as an application programming interface (API),

which provides a programmatic way to ask for subsets of a data set. This allows

the website owner to control who has access to the data, what portion of

the data they have access to, and how much data they can access. Typically,

the website owner will give you a token or key (a secret string of characters

somewhat like a password) that you have to provide when accessing the API.

Another interesting thought: websites themselves are data! When you type a URL into your browser window, your browser asks the web server (another computer on the internet whose job it is to respond to requests for the website) to give it the website’s data, and then your browser translates that data into something you can see. If the website shows you some information that you’re interested in, you could create a data set for yourself by copying and pasting that information into a file. This process of taking information directly from what a website displays is called web scraping (or sometimes screen scraping). Now, of course, copying and pasting information manually is a painstaking and error-prone process, especially when there is a lot of information to gather. So instead of asking your browser to translate the information that the web server provides into something you can see, you can collect that data programmatically—in the form of hypertext markup language (HTML) and cascading style sheet (CSS) code—and process it to extract useful information. HTML provides the basic structure of a site and tells the webpage how to display the content (e.g., titles, paragraphs, bullet lists etc.), whereas CSS helps style the content and tells the webpage how the HTML elements should be presented (e.g., colors, layouts, fonts etc.).

This subsection will show you the basics of both web scraping

with the BeautifulSoup Python package [Richardson, 2007]

and accessing the NASA “Astronomy Picture of the Day” API

using the requests Python package [Reitz and The Python Software Foundation, Accessed Online: 2023].

2.8.1. Web scraping#

HTML and CSS selectors#

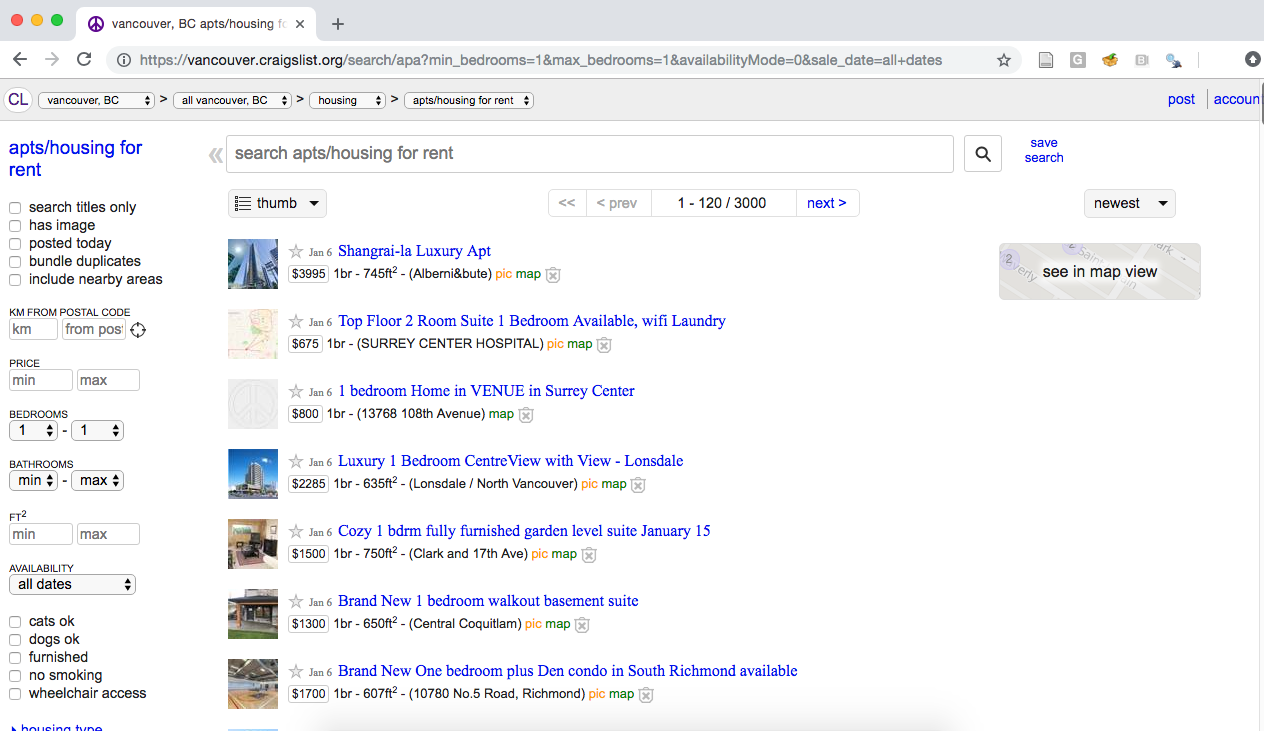

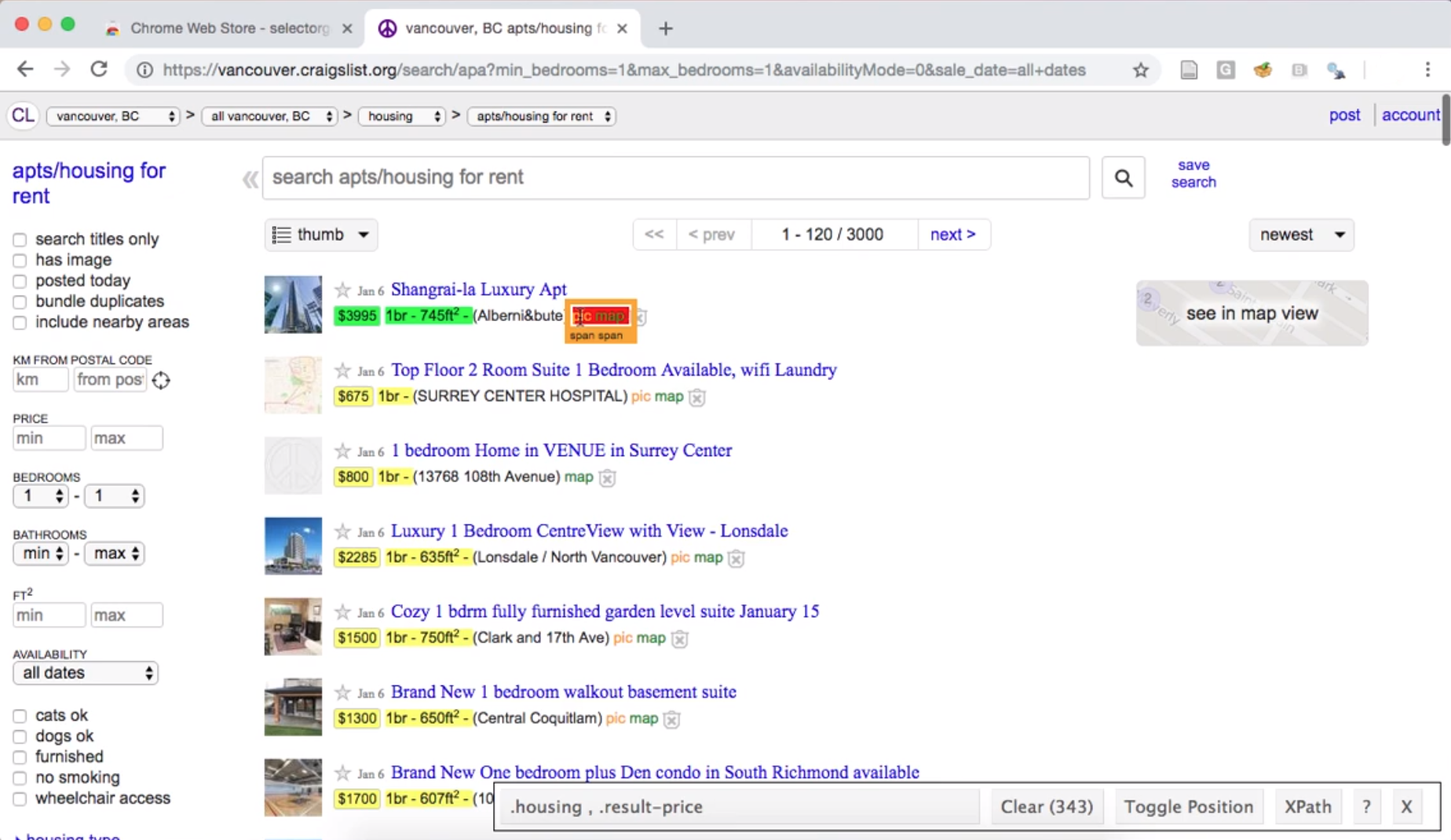

When you enter a URL into your browser, your browser connects to the web server at that URL and asks for the source code for the website. This is the data that the browser translates into something you can see; so if we are going to create our own data by scraping a website, we have to first understand what that data looks like! For example, let’s say we are interested in knowing the average rental price (per square foot) of the most recently available one-bedroom apartments in Vancouver on Craiglist. When we visit the Vancouver Craigslist website and search for one-bedroom apartments, we should see something similar to Fig. 2.2.

Fig. 2.2 Craigslist webpage of advertisements for one-bedroom apartments.#

Based on what our browser shows us, it’s pretty easy to find the size and price for each apartment listed. But we would like to be able to obtain that information using Python, without any manual human effort or copying and pasting. We do this by examining the source code that the web server actually sent our browser to display for us. We show a snippet of it below; the entire source is included with the code for this book:

<span class="result-meta">

<span class="result-price">$800</span>

<span class="housing">

1br -

</span>

<span class="result-hood"> (13768 108th Avenue)</span>

<span class="result-tags">

<span class="maptag" data-pid="6786042973">map</span>

</span>

<span class="banish icon icon-trash" role="button">

<span class="screen-reader-text">hide this posting</span>

</span>

<span class="unbanish icon icon-trash red" role="button"></span>

<a href="#" class="restore-link">

<span class="restore-narrow-text">restore</span>

<span class="restore-wide-text">restore this posting</span>

</a>

<span class="result-price">$2285</span>

</span>

Oof…you can tell that the source code for a web page is not really designed for humans to understand easily. However, if you look through it closely, you will find that the information we’re interested in is hidden among the muck. For example, near the top of the snippet above you can see a line that looks like

<span class="result-price">$800</span>

That snippet is definitely storing the price of a particular apartment. With some more investigation, you should be able to find things like the date and time of the listing, the address of the listing, and more. So this source code most likely contains all the information we are interested in!

Let’s dig into that line above a bit more. You can see that

that bit of code has an opening tag (words between < and >, like

<span>) and a closing tag (the same with a slash, like </span>). HTML

source code generally stores its data between opening and closing tags like

these. Tags are keywords that tell the web browser how to display or format

the content. Above you can see that the information we want ($800) is stored

between an opening and closing tag (<span> and </span>). In the opening

tag, you can also see a very useful “class” (a special word that is sometimes

included with opening tags): class="result-price". Since we want R to

programmatically sort through all of the source code for the website to find

apartment prices, maybe we can look for all the tags with the "result-price"

class, and grab the information between the opening and closing tag. Indeed,

take a look at another line of the source snippet above:

<span class="result-price">$2285</span>

It’s yet another price for an apartment listing, and the tags surrounding it

have the "result-price" class. Wonderful! Now that we know what pattern we

are looking for—a dollar amount between opening and closing tags that have the

"result-price" class—we should be able to use code to pull out all of the

matching patterns from the source code to obtain our data. This sort of “pattern”

is known as a CSS selector (where CSS stands for cascading style sheet).

The above was a simple example of “finding the pattern to look for”; many

websites are quite a bit larger and more complex, and so is their website

source code. Fortunately, there are tools available to make this process

easier. For example,

SelectorGadget is

an open-source tool that simplifies identifying the generating

and finding of CSS selectors.

At the end of the chapter in the additional resources section, we include a link to

a short video on how to install and use the SelectorGadget tool to

obtain CSS selectors for use in web scraping.

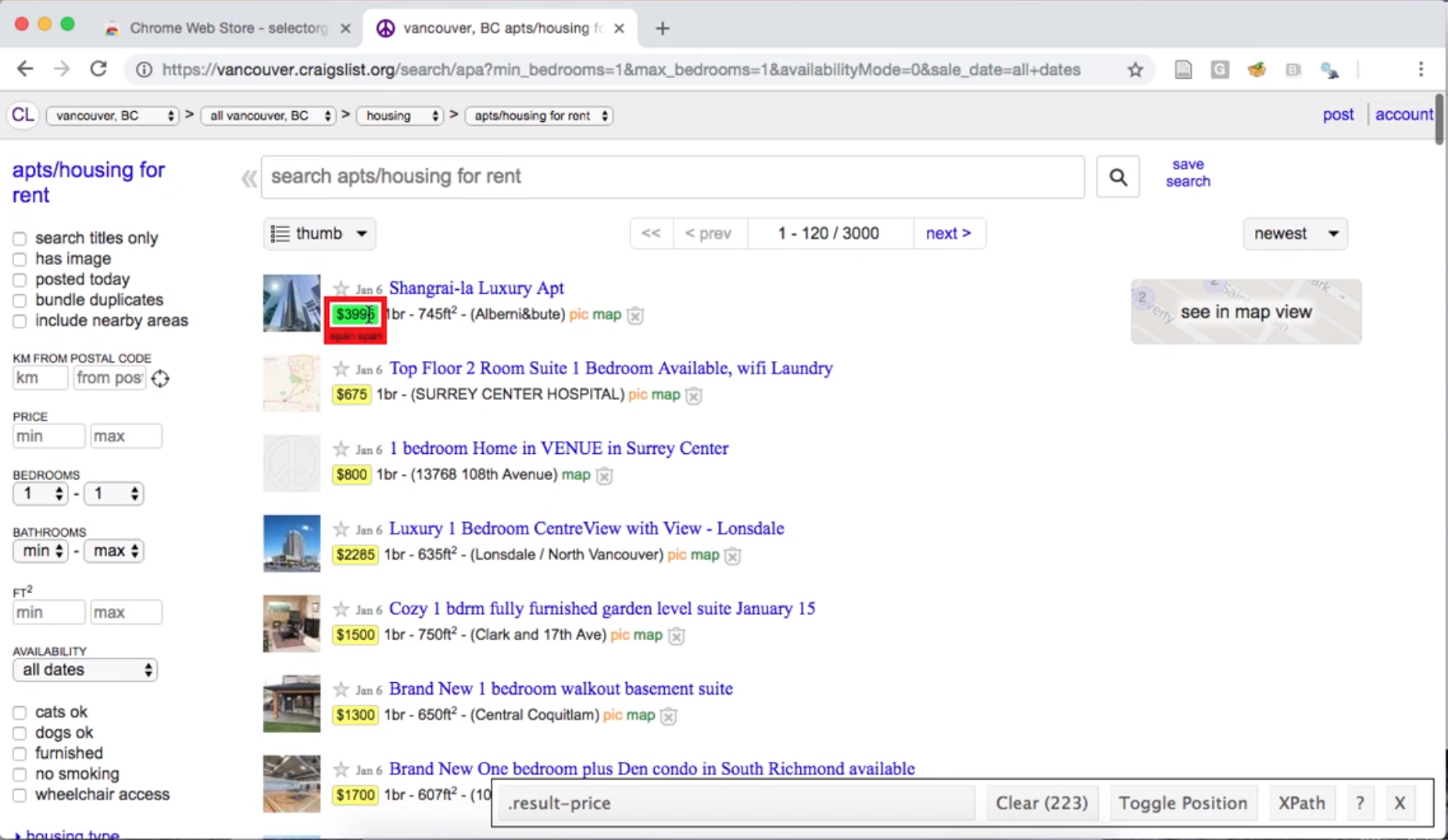

After installing and enabling the tool, you can click the

website element for which you want an appropriate selector. For

example, if we click the price of an apartment listing, we

find that SelectorGadget shows us the selector .result-price

in its toolbar, and highlights all the other apartment

prices that would be obtained using that selector (Fig. 2.3).

Fig. 2.3 Using the SelectorGadget on a Craigslist webpage to obtain the CCS selector useful for obtaining apartment prices.#

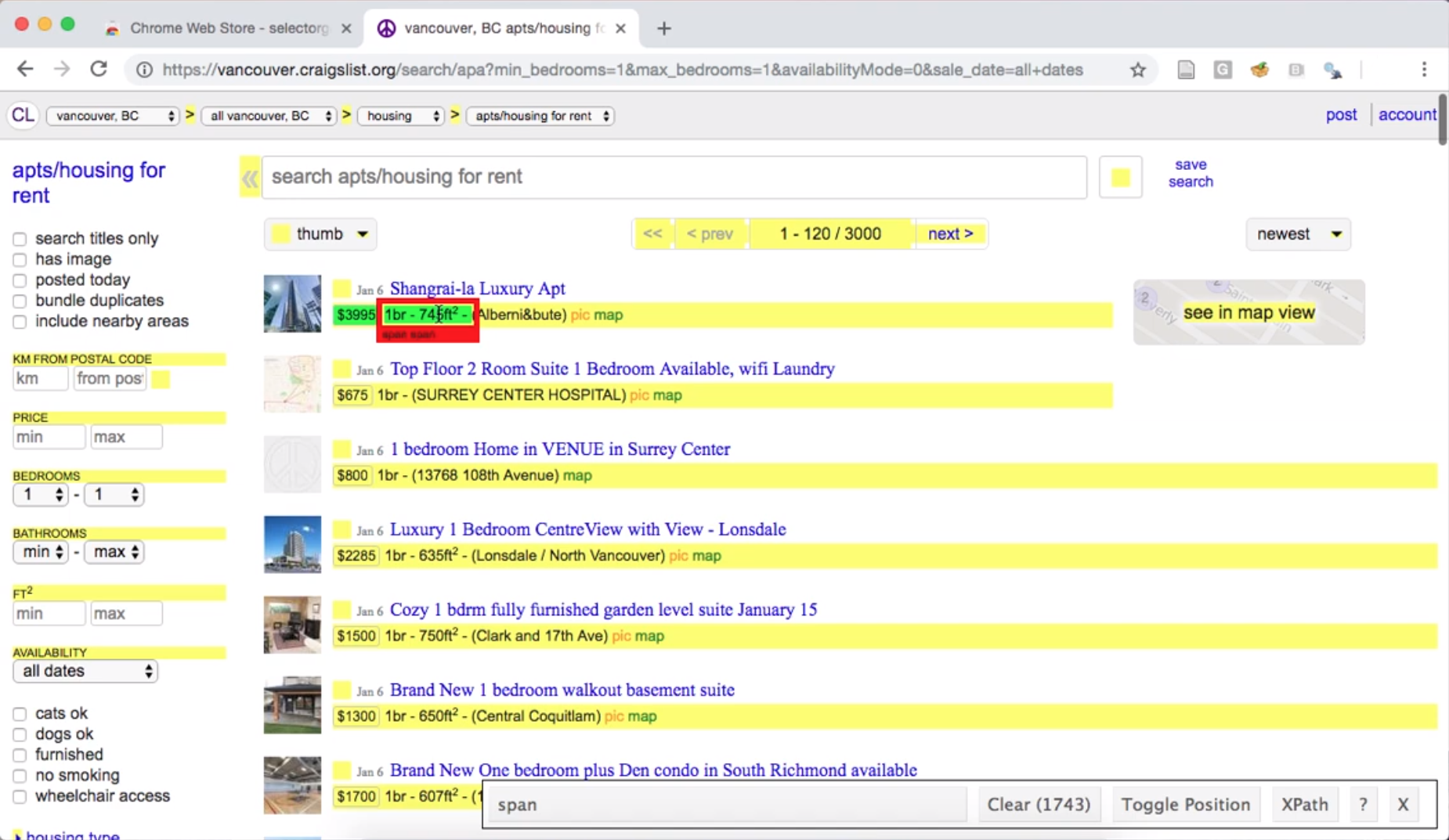

If we then click the size of an apartment listing, SelectorGadget shows us

the span selector, and highlights many of the lines on the page; this indicates that the

span selector is not specific enough to capture only apartment sizes (Fig. 2.4).

Fig. 2.4 Using the SelectorGadget on a Craigslist webpage to obtain a CCS selector useful for obtaining apartment sizes.#

To narrow the selector, we can click one of the highlighted elements that

we do not want. For example, we can deselect the “pic/map” links,

resulting in only the data we want highlighted using the .housing selector (Fig. 2.5).

Fig. 2.5 Using the SelectorGadget on a Craigslist webpage to refine the CCS selector to one that is most useful for obtaining apartment sizes.#

So to scrape information about the square footage and rental price

of apartment listings, we need to use

the two CSS selectors .housing and .result-price, respectively.

The selector gadget returns them to us as a comma-separated list (here

.housing , .result-price), which is exactly the format we need to provide to

Python if we are using more than one CSS selector.

Caution: are you allowed to scrape that website?

Before scraping data from the web, you should always check whether or not

you are allowed to scrape it! There are two documents that are important

for this: the robots.txt file and the Terms of Service

document. If we take a look at Craigslist’s Terms of Service document,

we find the following text: “You agree not to copy/collect CL content

via robots, spiders, scripts, scrapers, crawlers, or any automated or manual equivalent (e.g., by hand).”

So unfortunately, without explicit permission, we are not allowed to scrape the website.

What to do now? Well, we could ask the owner of Craigslist for permission to scrape. However, we are not likely to get a response, and even if we did they would not likely give us permission. The more realistic answer is that we simply cannot scrape Craigslist. If we still want to find data about rental prices in Vancouver, we must go elsewhere. To continue learning how to scrape data from the web, let’s instead scrape data on the population of Canadian cities from Wikipedia. We have checked the Terms of Service document, and it does not mention that web scraping is disallowed. We will use the SelectorGadget tool to pick elements that we are interested in (city names and population counts) and deselect others to indicate that we are not interested in them (province names), as shown in Fig. 2.6.

Fig. 2.6 Using the SelectorGadget on a Wikipedia webpage.#

We include a link to a short video tutorial on this process at the end of the chapter in the additional resources section. SelectorGadget provides in its toolbar the following list of CSS selectors to use:

td:nth-child(8) ,

td:nth-child(4) ,

.largestCities-cell-background+ td a

Now that we have the CSS selectors that describe the properties of the elements that we want to target, we can use them to find certain elements in web pages and extract data.

Scraping with BeautifulSoup#

We will use the requests and BeautifulSoup Python packages to scrape data

from the Wikipedia page. After loading those packages, we tell Python which

page we want to scrape by providing its URL in quotations to the requests.get

function. This function obtains the raw HTML of the page, which we then

pass to the BeautifulSoup function for parsing:

import requests

import bs4

wiki = requests.get("https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canada")

page = bs4.BeautifulSoup(wiki.content, "html.parser")

The requests.get function downloads the HTML source code for the page at the

URL you specify, just like your browser would if you navigated to this site.

But instead of displaying the website to you, the requests.get function just

returns the HTML source code itself—stored in the wiki.content

variable—which we then parse using BeautifulSoup and store in the

page variable. Next, we pass the CSS selectors we obtained from

SelectorGadget to the select method of the page object. Make sure to

surround the selectors with quotation marks; select expects that argument is

a string. We store the result of the select function in the population_nodes

variable. Note that select returns a list; below we slice the list to

print only the first 5 elements for clarity.

population_nodes = page.select(

"td:nth-child(8) , td:nth-child(4) , .largestCities-cell-background+ td a"

)

population_nodes[:5]

[<a href="/wiki/Greater_Toronto_Area" title="Greater Toronto Area">Toronto</a>,

<td style="text-align:right;">6,202,225</td>,

<a href="/wiki/London,_Ontario" title="London, Ontario">London</a>,

<td style="text-align:right;">543,551

</td>,

<a href="/wiki/Greater_Montreal" title="Greater Montreal">Montreal</a>]

Each of the items in the population_nodes list is a node from the HTML document that matches the CSS

selectors you specified. A node is an HTML tag pair (e.g., <td> and </td>

which defines the cell of a table) combined with the content stored between the

tags. For our CSS selector td:nth-child(4), an example node that would be

selected would be:

<td style="text-align:left;">

<a href="/wiki/London,_Ontario" title="London, Ontario">London</a>

</td>

Next, we extract the meaningful data—in other words, we get rid of the

HTML code syntax and tags—from the nodes using the get_text function.

In the case of the example node above, get_text function returns "London".

Once again we show only the first 5 elements for clarity.

[row.get_text() for row in population_nodes[:5]]

['Toronto', '6,202,225', 'London', '543,551\n', 'Montreal']

Fantastic! We seem to have extracted the data of interest from the raw HTML

source code. But we are not quite done; the data is not yet in an optimal

format for data analysis. Both the city names and population are encoded as

characters in a single vector, instead of being in a data frame with one

character column for city and one numeric column for population (like a

spreadsheet). Additionally, the populations contain commas (not useful for

programmatically dealing with numbers), and some even contain a line break

character at the end (\n). In Chapter 3, we will learn

more about how to wrangle data such as this into a more useful format for

data analysis using Python.

Scraping with read_html#

Using requests and BeautifulSoup to extract data based on CSS selectors is

a very general way to scrape data from the web, albeit perhaps a little bit

complicated. Fortunately, pandas provides the

read_html

function, which is easier method to try when the data

appear on the webpage already in a tabular format. The read_html function takes one

argument—the URL of the page to scrape—and will return a list of

data frames corresponding to all the tables it finds at that URL. We can see

below that read_html found 17 tables on the Wikipedia page for Canada.

canada_wiki_tables = pd.read_html("https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canada")

len(canada_wiki_tables)

17

After manually searching through these, we find that the table containing the

population counts of the largest metropolitan areas in Canada is contained in

index 1. We use the droplevel method to simplify the column names in the resulting

data frame:

canada_wiki_df = canada_wiki_tables[1]

canada_wiki_df.columns = canada_wiki_df.columns.droplevel()

canada_wiki_df

| Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | Rank.1 | Name.1 | Province.1 | Pop..1 | Unnamed: 8_level_1 | Unnamed: 9_level_1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | Toronto | Ontario | 6202225 | 11 | London | Ontario | 543551 | NaN | NaN |

| 1 | 2 | Montreal | Quebec | 4291732 | 12 | Halifax | Nova Scotia | 465703 | NaN | NaN |

| 2 | 3 | Vancouver | British Columbia | 2642825 | 13 | St. Catharines–Niagara | Ontario | 433604 | NaN | NaN |

| 3 | 4 | Ottawa–Gatineau | Ontario–Quebec | 1488307 | 14 | Windsor | Ontario | 422630 | NaN | NaN |

| 4 | 5 | Calgary | Alberta | 1481806 | 15 | Oshawa | Ontario | 415311 | NaN | NaN |

| 5 | 6 | Edmonton | Alberta | 1418118 | 16 | Victoria | British Columbia | 397237 | NaN | NaN |

| 6 | 7 | Quebec City | Quebec | 839311 | 17 | Saskatoon | Saskatchewan | 317480 | NaN | NaN |

| 7 | 8 | Winnipeg | Manitoba | 834678 | 18 | Regina | Saskatchewan | 249217 | NaN | NaN |

| 8 | 9 | Hamilton | Ontario | 785184 | 19 | Sherbrooke | Quebec | 227398 | NaN | NaN |

| 9 | 10 | Kitchener–Cambridge–Waterloo | Ontario | 575847 | 20 | Kelowna | British Columbia | 222162 | NaN | NaN |

Once again, we have managed to extract the data of interest from the raw HTML

source code—but this time using the convenient read_html function,

without needing to explicitly use CSS selectors! However, once again, we still

need to do some cleaning of this result. Referring back to Fig. 2.6,

we can see that the table is formatted with two sets of columns (e.g., Name

and Name.1) that we will need to somehow merge. In Chapter 3, we will learn more about how to wrangle data into a useful

format for data analysis.

2.8.2. Using an API#

Rather than posting a data file at a URL for you to download, many websites

these days provide an API that can be accessed through a programming language

like Python. The benefit of using an API is that data owners have much more control

over the data they provide to users. However, unlike web scraping, there is no

consistent way to access an API across websites. Every website typically has

its own API designed especially for its own use case. Therefore we will just

provide one example of accessing data through an API in this book, with the

hope that it gives you enough of a basic idea that you can learn how to use

another API if needed. In particular, in this book we will show you the basics

of how to use the requests package in Python to access data from the NASA “Astronomy Picture

of the Day” API (a great source of desktop backgrounds, by the way—take a look at the stunning

picture of the Rho-Ophiuchi cloud complex [NASA et al., Accessed Online: 2023] in Fig. 2.7 from July 13, 2023!).

Fig. 2.7 The James Webb Space Telescope’s NIRCam image of the Rho Ophiuchi molecular cloud complex.#

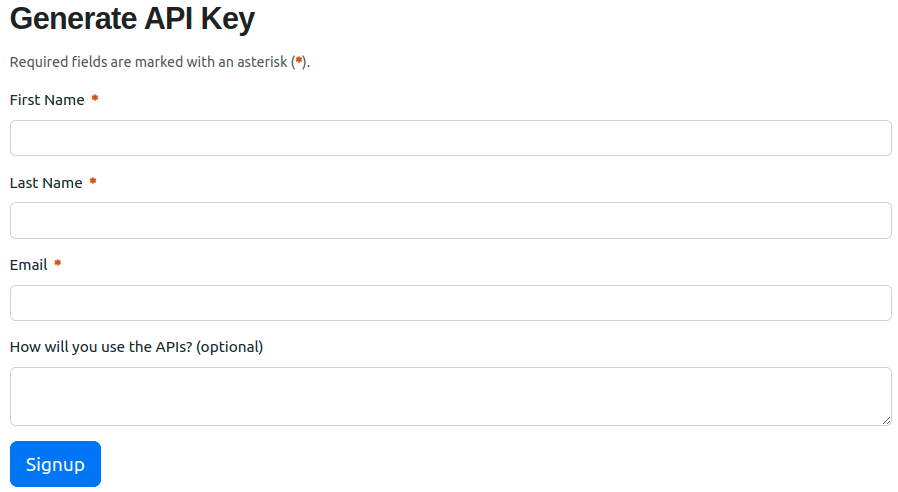

First, you will need to visit the NASA APIs page and generate an API key (i.e., a password used to identify you when accessing the API). Note that a valid email address is required to associate with the key. The signup form looks something like Fig. 2.8. After filling out the basic information, you will receive the token via email. Make sure to store the key in a safe place, and keep it private.

Fig. 2.8 Generating the API access token for the NASA API.#

Caution: think about your API usage carefully!

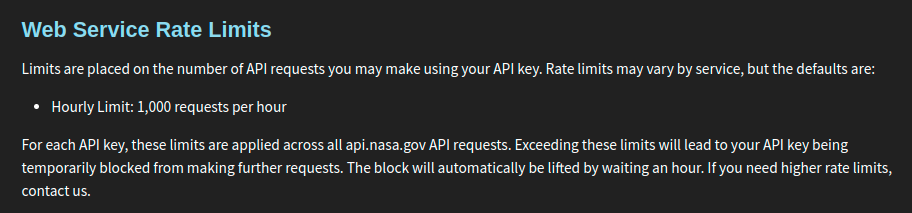

When you access an API, you are initiating a transfer of data from a web server to your computer. Web servers are expensive to run and do not have infinite resources. If you try to ask for too much data at once, you can use up a huge amount of the server’s bandwidth. If you try to ask for data too frequently—e.g., if you make many requests to the server in quick succession—you can also bog the server down and make it unable to talk to anyone else. Most servers have mechanisms to revoke your access if you are not careful, but you should try to prevent issues from happening in the first place by being extra careful with how you write and run your code. You should also keep in mind that when a website owner grants you API access, they also usually specify a limit (or quota) of how much data you can ask for. Be careful not to overrun your quota! So before we try to use the API, we will first visit the NASA website to see what limits we should abide by when using the API. These limits are outlined in Fig. 2.9.

Fig. 2.9 The NASA website specifies an hourly limit of 1,000 requests.#

After checking the NASA website, it seems like we can send at most 1,000 requests per hour. That should be more than enough for our purposes in this section.

Accessing the NASA API#

The NASA API is what is known as an HTTP API: this is a particularly common

kind of API, where you can obtain data simply by accessing a

particular URL as if it were a regular website. To make a query to the NASA

API, we need to specify three things. First, we specify the URL endpoint of

the API, which is simply a URL that helps the remote server understand which

API you are trying to access. NASA offers a variety of APIs, each with its own

endpoint; in the case of the NASA “Astronomy Picture of the Day” API, the URL

endpoint is https://api.nasa.gov/planetary/apod. Second, we write ?, which denotes that a

list of query parameters will follow. And finally, we specify a list of

query parameters of the form parameter=value, separated by & characters. The NASA

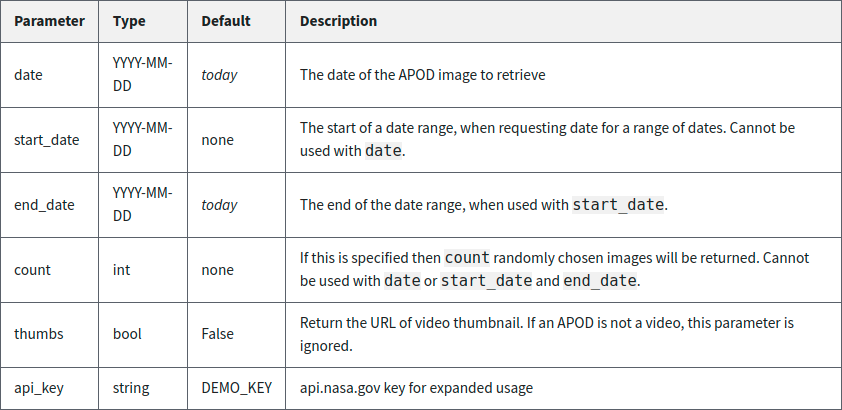

“Astronomy Picture of the Day” API accepts the parameters shown in

Fig. 2.10.

Fig. 2.10 The set of parameters that you can specify when querying the NASA “Astronomy Picture of the Day” API, along with syntax, default settings, and a description of each.#

So for example, to obtain the image of the day

from July 13, 2023, the API query would have two parameters: api_key=YOUR_API_KEY

and date=2023-07-13. Remember to replace YOUR_API_KEY with the API key you

received from NASA in your email! Putting it all together, the query will look like the following:

https://api.nasa.gov/planetary/apod?api_key=YOUR_API_KEY&date=2023-07-13

If you try putting this URL into your web browser, you’ll actually find that the server responds to your request with some text:

{"date":"2023-07-13","explanation":"A mere 390 light-years away, Sun-like stars

and future planetary systems are forming in the Rho Ophiuchi molecular cloud

complex, the closest star-forming region to our fair planet. The James Webb

Space Telescope's NIRCam peered into the nearby natal chaos to capture this

infrared image at an inspiring scale. The spectacular cosmic snapshot was

released to celebrate the successful first year of Webb's exploration of the

Universe. The frame spans less than a light-year across the Rho Ophiuchi region

and contains about 50 young stars. Brighter stars clearly sport Webb's

characteristic pattern of diffraction spikes. Huge jets of shocked molecular

hydrogen blasting from newborn stars are red in the image, with the large,

yellowish dusty cavity carved out by the energetic young star near its center.

Near some stars in the stunning image are shadows cast by their protoplanetary

disks.","hdurl":"https://apod.nasa.gov/apod/image/2307/STScI-01_RhoOph.png",

"media_type":"image","service_version":"v1","title":"Webb's

Rho Ophiuchi","url":"https://apod.nasa.gov/apod/image/2307/STScI-01_RhoOph1024.png"}

Neat! There is definitely some data there, but it’s a bit hard to

see what it all is. As it turns out, this is a common format for data called

JSON (JavaScript Object Notation). We won’t encounter this kind of data much in this book,

but for now you can interpret this data just like

you’d interpret a Python dictionary: these are key : value pairs separated by

commas. For example, if you look closely, you’ll see that the first entry is

"date":"2023-07-13", which indicates that we indeed successfully received

data corresponding to July 13, 2023.

So now our job is to do all of this programmatically in Python. We will load

the requests package, and make the query using the get function, which takes a single URL argument;

you will recognize the same query URL that we pasted into the browser earlier.

We will then obtain a JSON representation of the

response using the json method.

import requests

nasa_data_single = requests.get(

"https://api.nasa.gov/planetary/apod?api_key=YOUR_API_KEY&date=2023-07-13"

).json()

nasa_data_single

{'date': '2023-07-13',

'explanation': "A mere 390 light-years away, Sun-like stars and future planetary systems are forming in the Rho Ophiuchi molecular cloud complex, the closest star-forming region to our fair planet. The James Webb Space Telescope's NIRCam peered into the nearby natal chaos to capture this infrared image at an inspiring scale. The spectacular cosmic snapshot was released to celebrate the successful first year of Webb's exploration of the Universe. The frame spans less than a light-year across the Rho Ophiuchi region and contains about 50 young stars. Brighter stars clearly sport Webb's characteristic pattern of diffraction spikes. Huge jets of shocked molecular hydrogen blasting from newborn stars are red in the image, with the large, yellowish dusty cavity carved out by the energetic young star near its center. Near some stars in the stunning image are shadows cast by their protoplanetary disks.",

'hdurl': 'https://apod.nasa.gov/apod/image/2307/STScI-01_RhoOph.png',

'media_type': 'image',

'service_version': 'v1',

'title': "Webb's Rho Ophiuchi",

'url': 'https://apod.nasa.gov/apod/image/2307/STScI-01_RhoOph1024.png'}

We can obtain more records at once by using the start_date and end_date parameters, as

shown in the table of parameters in Fig. 2.10.

Let’s obtain all the records between May 1, 2023, and July 13, 2023, and store the result

in an object called nasa_data; now the response

will take the form of a Python list. Each item in the list will correspond to a single day’s record (just like the nasa_data_single object),

and there will be 74 items total, one for each day between the start and end dates:

nasa_data = requests.get(

"https://api.nasa.gov/planetary/apod?api_key=YOUR_API_KEY&start_date=2023-05-01&end_date=2023-07-13"

).json()

len(nasa_data)

74

For further data processing using the techniques in this book, you’ll need to turn this list of dictionaries

into a pandas data frame. Here we will extract the date, title, copyright, and url variables

from the JSON data, and construct a pandas DataFrame using the extracted information.

Note

Understanding this code is not required for the remainder of the textbook. It is included for those

readers who would like to parse JSON data into a pandas data frame in their own data analyses.

data_dict = {

"date":[],

"title": [],

"copyright" : [],

"url": []

}

for item in nasa_data:

if "copyright" not in item:

item["copyright"] = None

for entry in ["url", "title", "date", "copyright"]:

data_dict[entry].append(item[entry])

nasa_df = pd.DataFrame(data_dict)

nasa_df

| date | title | copyright | url | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2023-05-01 | Carina Nebula North | \nCarlos Taylor\n | https://apod.nasa.gov/apod/image/2305/CarNorth... |

| 1 | 2023-05-02 | Flat Rock Hills on Mars | \nNASA, \nJPL-Caltech, \nMSSS;\nProcessing: Ne... | https://apod.nasa.gov/apod/image/2305/FlatMars... |

| 2 | 2023-05-03 | Centaurus A: A Peculiar Island of Stars | \nMarco Lorenzi,\nAngus Lau & Tommy Tse; \nTex... | https://apod.nasa.gov/apod/image/2305/NGC5128_... |

| 3 | 2023-05-04 | The Galaxy, the Jet, and a Famous Black Hole | None | https://apod.nasa.gov/apod/image/2305/pia23122... |

| 4 | 2023-05-05 | Shackleton from ShadowCam | None | https://apod.nasa.gov/apod/image/2305/shacklet... |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 69 | 2023-07-09 | Doomed Star Eta Carinae | \nNASA, \nESA, \nHubble;\n Processing & \nLice... | https://apod.nasa.gov/apod/image/2307/EtaCarin... |

| 70 | 2023-07-10 | Stars, Dust and Nebula in NGC 6559 | \nAdam Block,\nTelescope Live\n | https://apod.nasa.gov/apod/image/2307/NGC6559_... |

| 71 | 2023-07-11 | Sunspots on an Active Sun | None | https://apod.nasa.gov/apod/image/2307/SpottedS... |

| 72 | 2023-07-12 | Rings and Bar of Spiral Galaxy NGC 1398 | None | https://apod.nasa.gov/apod/image/2307/Ngc1398_... |

| 73 | 2023-07-13 | Webb's Rho Ophiuchi | None | https://apod.nasa.gov/apod/image/2307/STScI-01... |

74 rows × 4 columns

Success—we have created a small data set using the NASA

API! This data is also quite different from what we obtained from web scraping;

the extracted information is readily available in a JSON format, as opposed to raw

HTML code (although not every API will provide data in such a nice format).

From this point onward, the nasa_df data frame is stored on your

machine, and you can play with it to your heart’s content. For example, you can use